The next sprout-based outbreak is upon us, again in Europe. Fenugreek seeds imported from Egypt have been identified as the source of an E coli outbreak in France this month.

According to a Wall Street Journal article, there is some evidence that Fenugreek from the same source were imported to Germany over the last couple years, and that the Fenugreek sprouts could be related to the German E. coli outbreak as well.

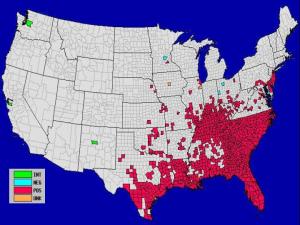

Back in the US, sprouts from an Idaho-based company were recalled last week. These sprouts have been linked to a 5-state outbreak of Salmonella enteritidis (states include Washington, Idaho, North Dakota, Montana, and New Jersey).

So, why the sprouts? Be they alfalfa or fenugreek or bean, these seemingly healthy raw-food options are the disease harbinger of the salad bar. In their US outbreak press release, the FDA warns that susceptible groups (elderly, infants, immune compromised…) should avoid eating any sprouts altogether, ever. According to FoodSafety.gov and others, there are a few reasons that sprouts pose a higher risk than your average raw food:

- Aflalfa fields may be fertilized with manure, which can contaminate seeds later used for sprouting

- Seeds not contaminated in the field may be contaminated during storage

- Bacterial contaimination of a seed intended for sprouting can survive if proper control techniques are not practiced during harvest and storage

- Sprouts require warm, moist conditions to germinate — also a favorite habitat of bacteria

CDC recommends cooking sprouts before consumption (yuk!), and others note that home grown sprouts are not necessarily less contaminated. For many people in the know, sprouts are off the table.